The White Mayfly

My immediate suspicion was confirmed when I saw the photo that was sent with it, in which countless insect corpses covered the roadsides on the bridge over the Enz River: Ephoron virgo, the European white mayfly! One must know: Each time the name “White Mayfly” is mentioned, a pleasant shiver runs down the spine of insiders, because this animal brings back memories of better times for insects. Ephoron virgo is a mayfly, which in past centuries was famous for its summerly mass flights at the lower reaches of larger European rivers.

In 1757, Jacob Schäffer reported in his treatise „Vom fliegenden Uferaas, wegen desselben am elften Augustmon. an der Donau, und sonderlich auf der steinernen Brücke, zu Regensburg ausserordentlich häufigen Erscheinung und Fluges“: On the 11th of the present month August, in the evening at around 11 o’clock, because it was very humid, and there was a strong thunderstorm in the sky, an enormous number of strange and unknown flies, or birds, as some had called it, rained down. The same would have fallen down, amongst various places of the Danube stream, especially so on the local stone bridge, at such a height that they would not only have covered all the stones completely, but would also have lain now and then 2 to 3 inches high atop one another. Whoever walked or stood on the bridge at this time would have been completely white, as if it snowed upon them.“

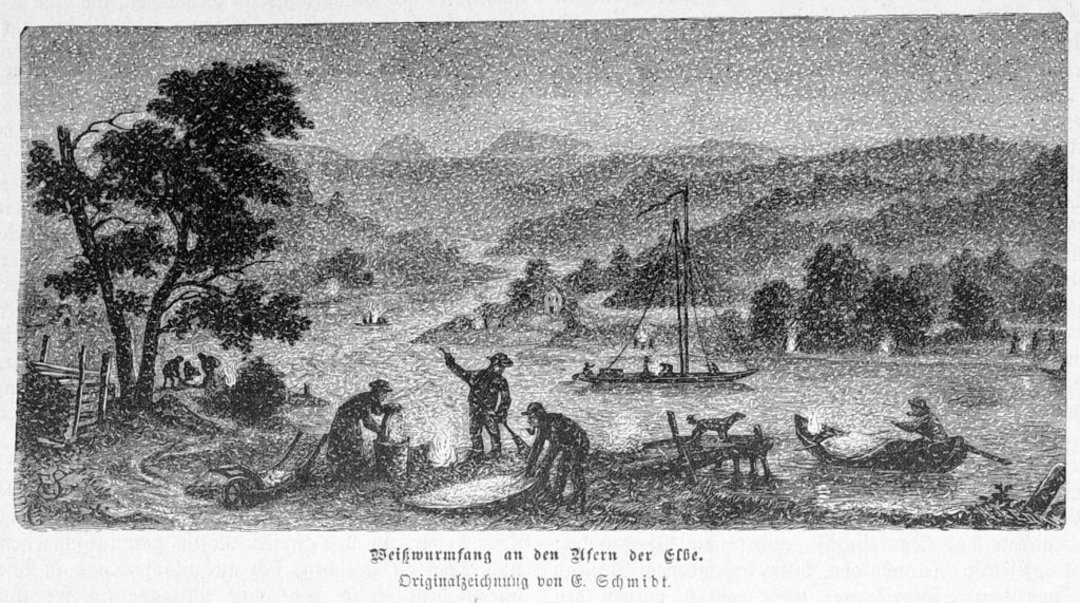

What Jacob Schäffer in Regensburg was astonished about was known to every local on the Elbe in the 19th century: fires were lit at regular intervals along the river to attract the hatching “whiteworms”, which rose from the middle of the water after sunset. Karl Russ wrote in 1887 in the then popular magazine “Die Gartenlaube”: “According to traditional custom, without quarrelling or bickering, people took possession of one place each on the riverbank, built a square stove about 3 meters in size, directly by the water and a little into the stream, built a small fireplace in the middle and laid an old wire netting on top of it. On top of it they put a wide, earthen pot without a bottom and light up in this pinewood. Soon the drakes swarm each fire by the millions like snowflakes, fall down with scorched wings onto sackcloth spread out all around, are swept together and poured into baskets… The drakes, which have dried in the air and been freed from their wings by shaking and blowing off, are now marketed as white worms.“ The animals were not only used as fish bait or food for cage birds. Farmers also fed the vast amounts of insects to the pigs or even spread them on the fields as fertilizer.

Comments (0)

No Comments