The discovery

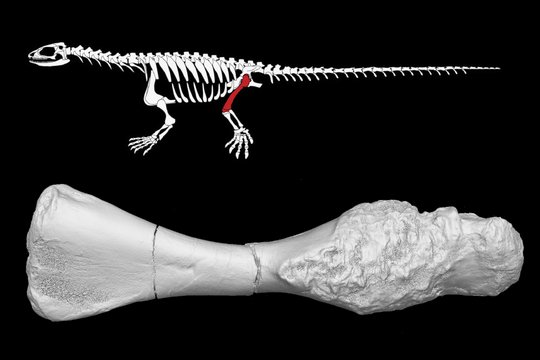

For me the adventure began during my PhD, a bit more than ten years ago. Back then I was in Paris, at the Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle. A friend and colleague of mine, Manuel Martínez-Cáceres, came back from his last trip from Peru with a surprise: a few thin-sections. He told me that the field palaeontologists have found something very weird in the Ica desert (Southern Peru). Mario Urbina, who made the initially discovery, is usually able to recognise right away what he finds, because he has been excavating these dunes for several decades. But this time was different. What was sticking out of the rock was big and weirdly shaped, and lacked the porosity usually seen in fossil bone. Some of his colleagues told him “this does not look like a fossil, it might just be a rock”– but he is a stubborn character, and organised for some thin-sections to be made, to clarify the mystery. Those were the thin-sections I had in front of me back then, and the conclusion was clear: they were entirely made out of compact bone.

Comments (0)

No Comments